Introduction

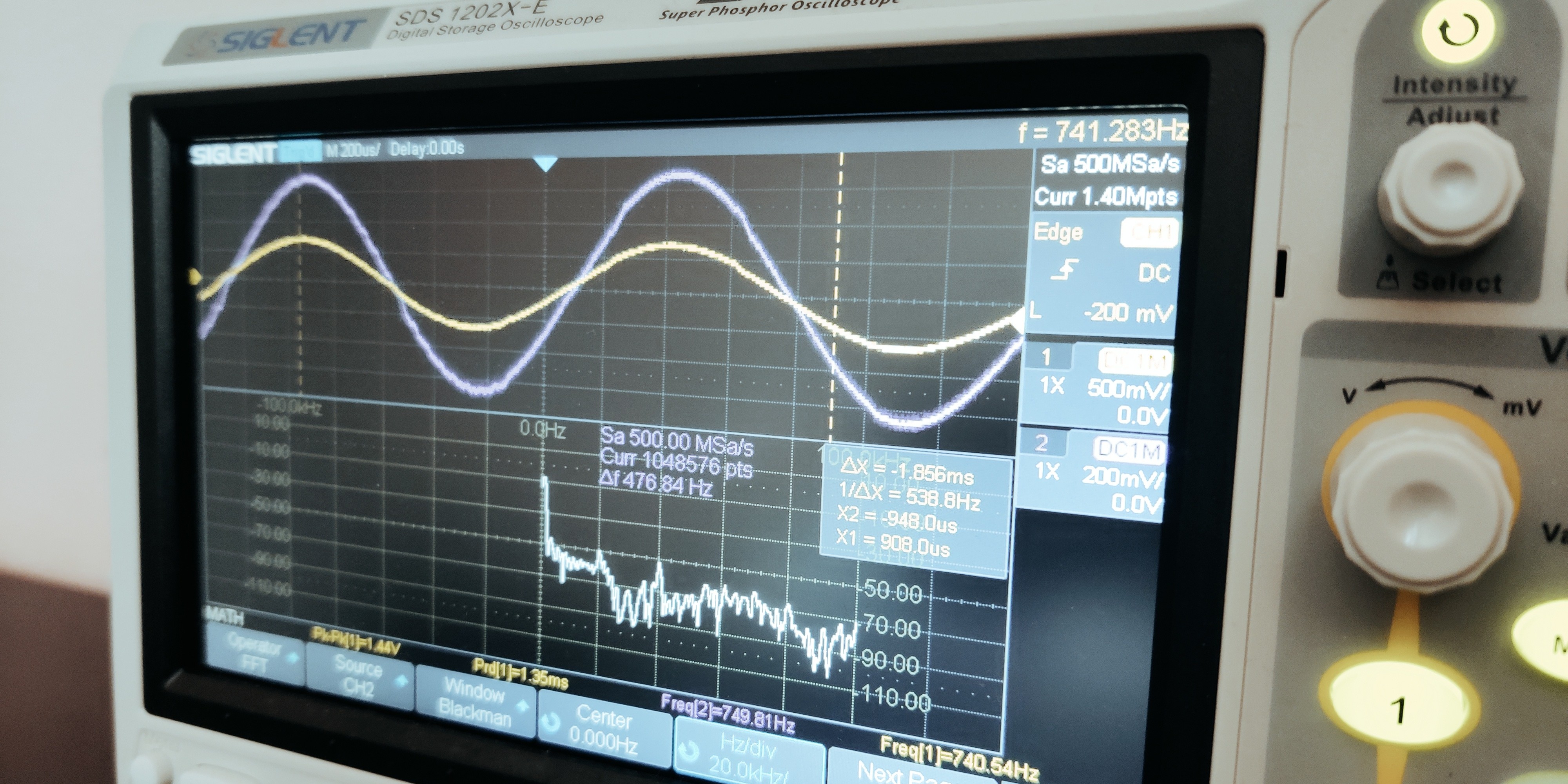

Last time we did together a circuit using verilog to communicate to a I2S device. But we never delved into how to make a waveform for it.

Now, don’t get me wrong: if you did the blinky led example while starting your first projects, this can be easily achievable for you:

- A square pattern is just zeros and ones

- A saw pattern is a counter from zero to max

- A triangle wave is a counter that goes back after hitting max or min values

- A sine wave is just some CORDIC…

Now, we will not be using CORDIC and will not be doing simple counters. I want to show you a couple of tricks to generate a clean sine waveform that you can later compose to create more fancy sounds.

Single LUT1

Instead of CORDIC, we will encode the values of the sine function within a lookup table (LUT) and then use the values and transform them as needed. This will allow us to create a shape that resembles the trigonometric function, just without frequency content. Instead, for the frequency we will use a counter and call it phase accumulator because it sounds better. This counter will keep track of the phase per time step (clock or strobe), hence the frequency will be directly a ratio between the phase advancement and this time step.

Sine ROM

Let’s take a look at the ROM:

| |

In here, I encoded the values of the sine function from zero to pi/2. This is because to save memory and resource, we would rather leverage on the sine symmetries and make a little calculation depending on the phase.

The resolution of this function is 8bit and there are 64 values. This means that using the symmetries, we add a sign, making a 9bit value for a total of 256 samples per period. If we use as sampling rate the same we used in the former blog about I2S, so 48KHz, that means that a full period will be of 48KHz/256 or 187.5Hz. This basically defines the frequency resolution, and as such, I don’t like this number. So I will boost artificially the number of samples in the LUT by using linear interpolation. This interpolation at the same time will boost by additional bits the resolution of the signal with some penalty on the Signal to Noise plus Distortion Ratio (SNDR) with respect to use a bigger and more accurate LUT, but with huge savings in power, area and complexity.

Synthesizer

We use this sine ROM with a circuit that fetch the values by encoding the phase into a memory address and transforms it into a complete waveform. So let’s put some framework to begin with:

| |

We have as inputs a clock, that for compatibility with the I2S circuit, will be 60MHz, we will need a volume control, the phase step per time step (proxy of the frequency) and put out the current value of the numerical oscillator.

Let’s see how to make this quarter of wave into a complete wave:

| |

Not sure if intuitive enough, but basically two things happen in here:

- On even quadrants the address to the room goes to the other side to have continuity after pi/2 and 3pi/2.

- On third and fourth quadrant, the sine changes sign, hence we add this sign and transform into 2-complement signed value

Then, we update via synchronous logic the strobe (to convert from 60MHz to 48KHz), the phase accumulator and keep track of the last value of the ROM. Consider that we will move only forward in phase here.

| |

You can see, data_last changes only when the data from the calculation made on the ROM values changes itself. This value will be used for linear interpolation.

Linear interpolation

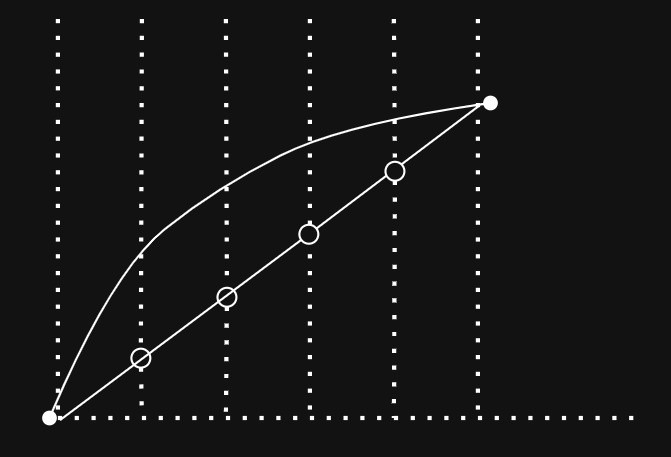

Let’s put it blunt in here because either you know what it is, or you don’t: between two points on the sine table, we will draw a line and divide it by a power of two number of points. This is not necessarily a good approximation, but the quantization error made is way smaller with respect to not doing anything.

The white dots are the values in the LUT, the curve is the theoretical values of the function in continuous time, the black dots are inferred from a line between the white dots.

The values at the middle points between two values of the LUT follow a simple linear relationship. Basically divide the $\Delta Y$ by the $\Delta \phi = X_{n+1} - X_{n}$ to obtain the slope, then multiply by the current slice in the phase and add the last value:

$$ Y_n = \frac{Y_{n+1} - Y_{n}}{X_{n+1} - X_{n}}m $$

here, $m$ is the current slice between 2 points in the LUT. We will choose a power of 2 for the maximum value of $m$ for simplicity, but it can be any value. The trick here, is that the maximum value of $m$ is equivalent to the number of slices between $X_{n+1} - X_{n}$, and if this value is a power of 2, then the division becomes a left shift. Actually, we don’t even have to do this shift, as the data is 9bit (8 + 1 of sign) and we extended by additional 15bit up to 24bit. Hence, we can just make a rest and call it a day. Then, what we do instead is leverage on the 18bit phase accumulator and make the next partition:

- bit

[17:16]tracks the sine quadrant - bit

[15:10]tracks the address in the sine ROM - bit

[9:0]are used for interpolation

So we can assume 18bit data with huge chunks of quantization, shift back 10bit, subtract, then multiply by the interpolation partition that tracks the current slice between to ROM points. The data is already shifted so few less circuits for us.

With 10 bits of interpolation, we are converting the 8bit ROM data into 18bit, add one for the sign, and then we can multiply this value for the volume setting, getting a total of 24bit data to the I2S circuit.

Neat, isn’t?

One more notes about the interpolation: by using the multiplication with this recipe, we are leveraging on the DSP slices in the Artix 7 FPGA, there are something like 120 or so of those slices, so they are kind of precious and is better to save them for critical calculations. In this example we just used two of those for a synthesizer.

Conclusion

This is just a toy example of how to make a LUT based synthesizer. More improvements can be made and perhaps I will. You can send this 24bit data and chain it with the I2C circuit we did last time, put headphones and listen the result.

As usual, if you want to get the sources of these blocks, as I write this blog I will place them at my github repo

Disclaimer: don’t abbreviate the word “Single” please. ↩︎