Introduction

So, after you are done with the book and implemented your first 8-bit CPU you keep wondering

ok, but now I want to do real world stuff

Here I got you back, nothing comes before when it comes to real world stuff that having the capability of sending data to/from other devices. When I began my personal projects, when I got my Arty A7, I thought that I needed to be able to debug what’s happening inside the FPGA when the internal logic analyzer might not be too reliable (pro-tip: it’s very reliable). So being able to send to a computer data using a simple protocol is a must.

UART comes as the best option for easy communication, as the baudrate is not too high to need complicated timing analysis, but complex enough to be a funny first project to learn the basics of digital design applied to real world, with real constraints and specifications.

What is this UART then?

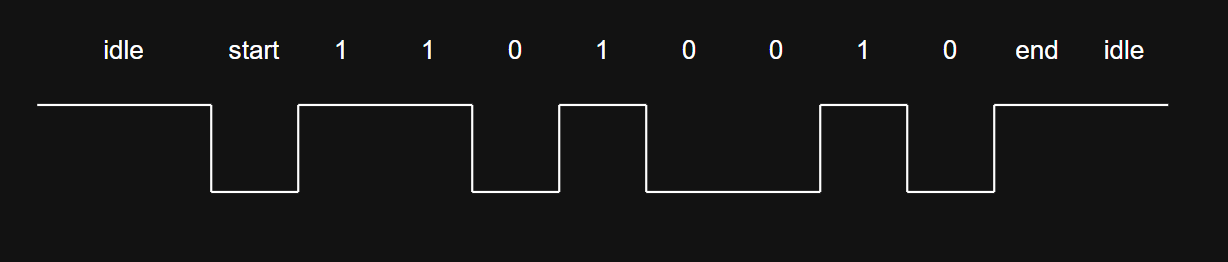

UART (universal asynchronous receiver-transmitter) is a serial protocol of communication that doesn’t require tight clock sync between transmitter (TX) and receiver (RX). Basically, the TX pulls the wire down to tell the RX that it needs to start listening, sends some bits of data one at time, maybe some parity bits and ends the transmission by setting the wire to high. Indeed, the wire is in resting state when it’s kept high.

Example of UART signal

As you can see from the picture, 8 bits are sent, no parity bit is sent, there is the starting signal (pull down) and the end signal (pull up). The transmission is in idle when the wire is kept high. The other condition is that the least significant bit (LSB) is sent first. For example, in the transmission above, the byte 8'h4B will be sent starting by the h4 symbol, just reversed, later the hB symbol, reversed as well.

How do I implement the UART thing?

Even before writing a single line of code, let’s put down a strategy on how to make this block and also how to verify it.

Functional blocks

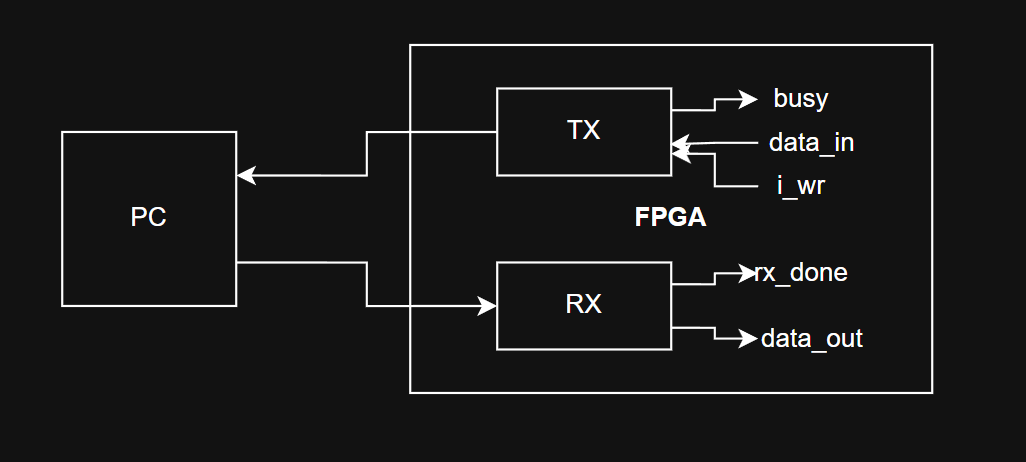

So, we have for the UART the transmitter TX and the receiver RX. The properties of those blocks should be such when there is a signal to enable communication they will start processing in a blocking way, that means they will process one byte at time and notify when this processing is finished so that the next one can start. From a top level perspective, we have then:

UART blocks

Basically, we will need two blocks: the TX that will get the data, the starting signal and return the UART stream to the PC and a notification when it’s done, and the RX that will get the incoming stream from the PC and notify when it’s done, providing the data at it’s output.

How do I verify this is working?

We will have to prepare a testbench, where we will chain some UART input data, use the RX to decode the stream, then send this very same data to the TX, where the expected result should be a UART stream that is equal but delayed as the input signal, very easy for verification, but since I’m kind of lazy, I will chain another RX, and make sure that the chaining of data->RX->TX->RX yields the same decoded data.

So, let’s see at the details of each block now

TX

The TX, as indicated in the picture above, takes an input data from a register, the order to start transmitting, and it will raise a busy flag while it’s serializing the data to indicate a potential FIFO or whatever is feeding with data the TX to not send any more until the flag is lowered. However, the TX should be ready to start as soon as it’s finished. For this, it comes to help the ending bit: while it’s pulled up for one period, the TX gets ready to receive the next byte of data.

To do this, we will rely on a finite state machine (FSM from now on), indicating at what step of the process the transmitter is. We will also be indicating at the block the baud rate for the transmission and since I’m using for this particular example the clock of the Arty A7 (100MHz), I will indicate this as a parameter. The goal is to tell the circuit, via a counter, how many clock cycles each period of the UART signal requires to transition to the next state

| |

The strobe signal is this counter, and when the counter reaches the required number of clock cycles, it will reset and command the next state to take over. Also, you can see I’m not explicitly indicating the final state, as I will consider as an idle state that will be capable of already receiving commands for the next byte to be transmitted.

For the sake of verification on simulation, I will be indicating an initial state for some variables. Those lines aren’t necessarily synthesizable, but are of great help and will avoid a lot of debugging later on simulation. Then, the main process is placed under a flip-flop (that posedge mixed with reg in its content). As you can see, when the strobe reach zero, the state is updated, the counter is reset to the value of DIVISOR and the output is set to the newest bit, else it will keep counting down. Another feature, if we are in the IDLE state we don’t count, the circuit is frozen. This is not that useful but I don’t like polar bears swimming around Italy because global warming.

| |

Finally, we define the transitions of the state machine and assign the busy flag up whenever we are busy processing data. Also, notice we are updating the temp_buf as a shift register. This is another subtlety, as it’s more expensive to place many switches on the place of the requested array than just shift the data and take the last bit. This will also help with filling with 1'b1s, so that

| |

There you got, as promised an easy block, few lines of HDL where we abide to basic rules of digital design. Now let’s take a look at the receiver

RX

This block is not more complicated, but it has a subtletly: a real line when idle, for any reason, can be pulled by noise, cross talking, electromagnetic interference, etc. into a low state. This is a false positive for the starting of the transmission and we don’t want to catch it. Also, unlike the transmitter, we want to sample the data not at the begining but at the middle of the UART period, this is because you never know the quality of the signal you are receiving, and if the cable is very long, lossy or don’t have enough power to driver the RX input capacitance, the signal might not settle correctly if we don’t give it enough time.

So, in the same ways as before, we define some parameters for the baud rate, the initial value of some variables and the states of the RX:

| |

The logic on the state machine. Same as before, if the state is in IDLE we just stop the counter. Here, we also define the rule for updating the output in such a way that hides the inner process, setting it at the final value only when we are about to set the state into idling.

| |

Finally, the update rules for the FSM, and we set the flag for the rx_done to one, but only for one clock cycle. This is because this way I can chain a RX and a TX and make echo requests with the UART. Also, notice that we set the next_state at the middle of the counter for the reasons indicated at the beginning of this section

| |

Simulation

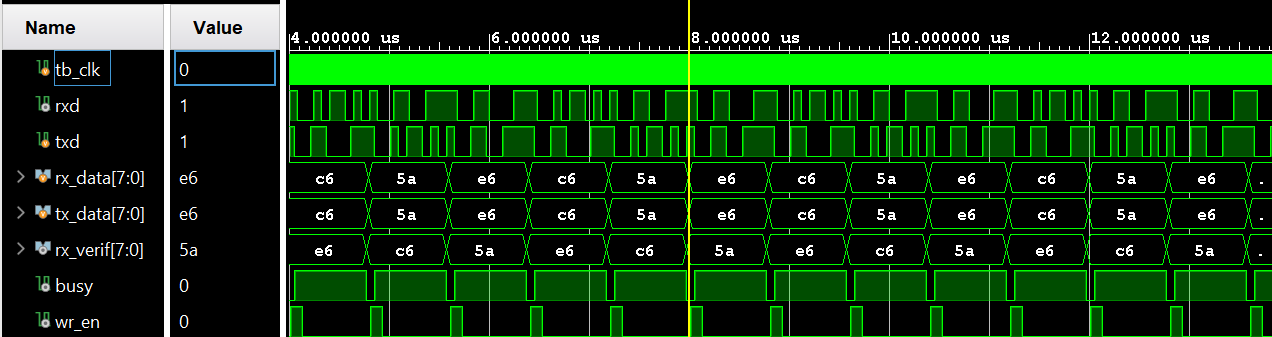

For testing this block, I will feed the RX with some premade data stream, and chain RX to TX to RX and check the values of the processed data and the UART signals. Also, via parameter, I will set the baud rate of the UART to 25Mbaud, so that the counter needs to count 4 clocks and the simulation doesn’t get too long.

| |

The resulting signals are as follows:

UART Simulation in Vivado

In the picture you can see the RX received the stream defined in reg [29:0] pattern and when it’s done it pass directly the data to the TX, then the TX will process and send the data to the verification RX, hence there will be a delay from TX to verification RX of about 9 symbols, without wasting clock cycles between one byte and another.

Conclusion

Together with you, this is the first block I created in my Arty A7 that I can consider a complete project. It pass a complete run of simulation and when implemented in the FPGA the echo functionality works. My next steps it’s to stress test this block by making a loop and sending pseudo-random data while checking the bit error rate.

If you want to get the sources of these blocks, as I write this blog I will place them at my github repo